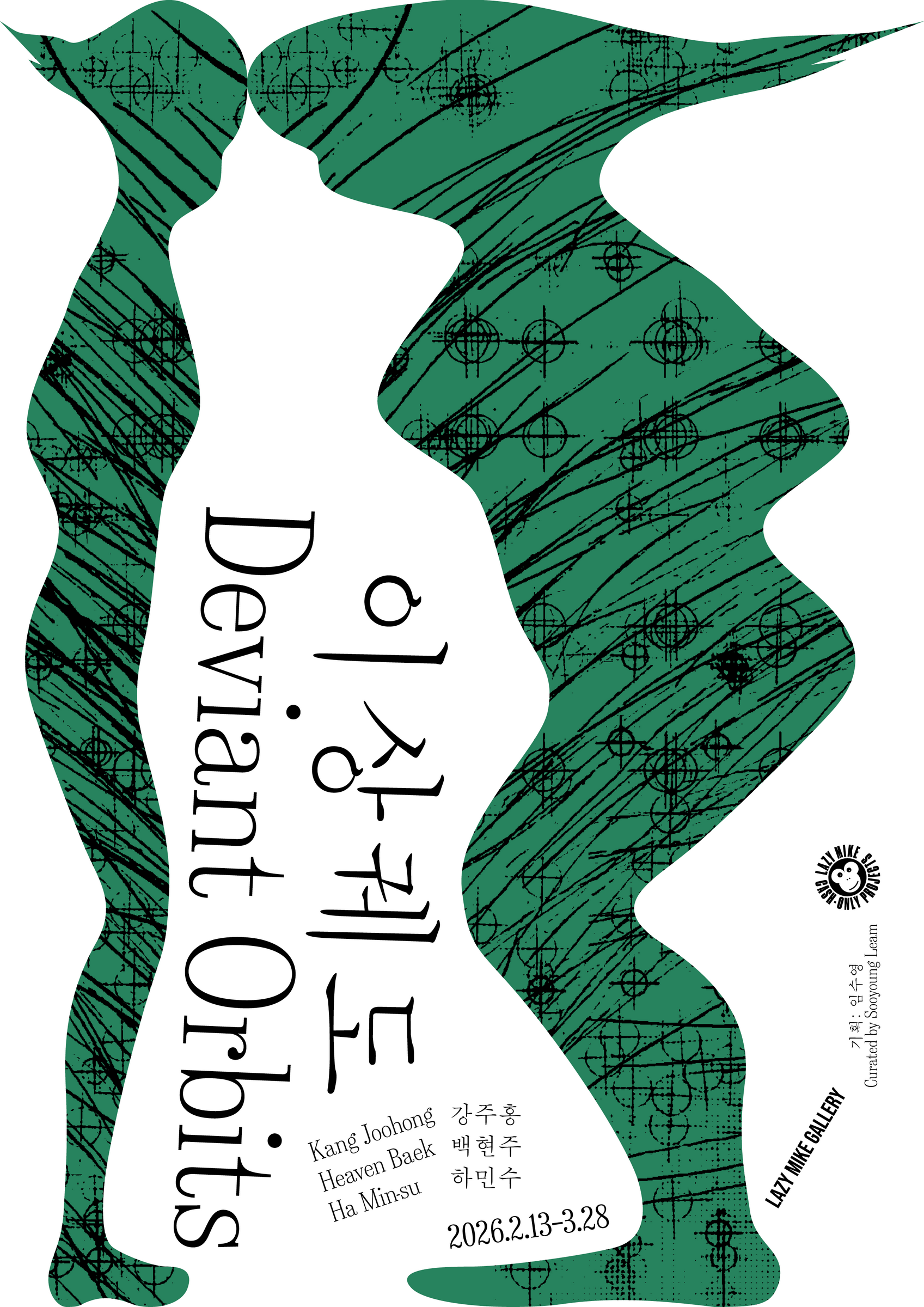

Deviant Orbits - Kang Joohong, Heaven Baek, Ha Minsu

February 13 , 2026 – March 28, 2026

February 13 , 2026 – March 28, 2026

Lazy Mike presents Deviant Orbits, a group exhibition featuring works by Kang Joohong, Heaven Baek, and Ha Minsu. Curated by Sooyoung Leam, the exhibition revisits what has been excluded or classified within social and institutional systems. It examines the desire for categorization embedded in archives, libraries, media, and other modes of record-keeping, while unsettling the fixed frameworks historically assigned to artists and their practices.

Deviant Orbits

So, by the damned, I mean the excluded.

But by the excluded I mean that which will some day be the excluding.

Or everything that is, won’t be.

And everything that isn’t, will be—

But, of course, will be that which won’t be—[1]

In 1919, the American writer and collector Charles Fort (1874–1932) published his first book, The Book of the Damned. Ominous from its very title, the volume is filled with what Fort called “damned data,” gathered over the course of twenty-seven years spent combing through magazines, newspapers, and journals in the libraries and museum archives of New York.[2] Having worked as a daily newspaper reporter before inheriting his father’s estate in middle age and devoting himself entirely to collecting, Fort focused on data that mainstream science had excluded or deemed logically inexplicable. Casting himself as a kind of amateur detective, he obsessively compiled and organized records of phenomena that scientists had largely ignored—ranging from unidentified flying objects and reports of animals or materials raining from the sky, to anomalous weather patterns and mysterious disappearances. Through this process, Fort imagined a defiant “procession” of facts cast aside by the arbitrary standards and categories imposed by society.[3] Yet he also seems to have recognized the paradox that any attempt to absorb the so-called “marginal” into the “mainstream” inevitably produces new forms of exclusion and marginalization. As he declares in the book’s opening lines, even “the damned” will one day return to “the position of the excluding.”

If Fort’s writing continues to resonate today, it may be because systems of classification grounded in reason and ideology are being produced ever more compulsively under the banners of efficiency, control, and prediction. That which is blurred, ambiguous, or resistant to language no longer remains merely in a “position of exclusion,” but is increasingly pushed outside the realm of knowledge altogether. What cannot be indexed within the boundaries drawn by society is now often treated as if it does not exist. Art is no exception. Conceived through the collaboration of three women artists, Kang Joohong, Heaven Baek, and Ha Minsu, alongside a curator and a gallerist, Deviant Orbits takes shape within these very dynamics of visibility. On one axis, the exhibition attends to the classificatory systems and conventions that have long been in place, and on another, overlays the multiple categories assigned to artists and their works in order to reconsider how these frameworks operate.[4]

The title of this exhibition is partly drawn from Marriage–Deviant Orbit, the sixth group exhibition organized by the artist collective 30 Carat, which Ha Minsu formed in 1993 together with women artists in their thirties whom she described as “continuing their work while sustaining inner growth.”[5] 30 Carat emerged from Ha’s earlier involvement with META-VOX, a group that pursued formal experimentation under the banner of the “tal-modern,” seeking to move beyond both 1980s modernism and Minjung Art.[6] Rather than functioning as a simple citation, the present exhibition returns to this earlier title as a deliberate reworking. Within the canon of Korean feminist art history, 30 Carat and the women’s movement of the 1990s remain indispensable points of reference for understanding Ha’s practice; yet at the same time, they have often functioned as frames that bind and delimit her work. The decision to revisit and adapt the title of a past exhibition emerges precisely from this tension. Deviant Orbits acknowledges the multiple categories and references that have been historically assigned to artists, while at the same time placing them in new relational configurations marked by differing speeds and directions. Here, “orbit” operates as a key metaphor—not as a boundary of classification, but as an indication of forces that push and pull, shaping conditions of movement and relation. The notion of an “deviant orbit,” moreover, conjures the possibility of slipping away from a prescribed trajectory altogether, suggesting a sudden and irregular deviation from what appears stable or given.

Each of the three artists has engaged with the institutional structures of archives, libraries, museums, and journalism, using these frameworks to examine classificatory ways of seeing individuals and entities. For instance, Kang Joohong’s practice has long examined and reconfigured print media, books, and library systems. On the first floor of the gallery, she presents Footnote 000–999 (2025), a work composed of bibliographic references drawn from the books she selected while translating the entire collection of the National Library of Korea into painting. These references are spread across the space, arranged like footnotes detached from a central text. She also layers Vanished Manuscript (2024) across walls and windows, repeatedly varying registration marks through silkscreen printing and brushwork to interchange the roles of print and painting. Conceived at a moment when her sustained engagement with the systems of libraries and museums returned as a sense of “fatigue and emptiness,” John Berger to Luise Luthi (2024) turns away from external institutions toward a more intimate terrain, taking as its material two books drawn from the artist’s own bookshelf.[7]

This self-reflective stance is articulated with particular intensity in Ha Minsu’s Looking at Myself (2014), in which a woman gazing at her reflection in water is rendered through soft fabric and tightly stitched thread. Long attentive to the ways in which mainstream media render certain events and lives visible through news reporting—while others are marginalized or erased in the process—Ha presents in this exhibition two series developed during the pandemic: Beside–Neighbor (2021) and People Are Dancing (2022). Addressing not only the structural conditions surrounding women but also the broader forms of social isolation and discrimination that produce what she has described as a “sad culture,” Ha employs slow, time-intensive processes of stitching to inscribe duration onto fabric, gradually calling marginalized presences into view.[8] Drawing from Korean traditional dance to capture bodies passing through periods of hardship, People Are Dancing goes beyond simply remembering those who have been excluded or forgotten, revealing the artist’s wish to restore to them a rhythm of liberation.

By contrast, Heaven Baek’s work temporarily brings into presence figures that have long been mediated through the recording apparatuses of the nation-state and empire. Sound travels across the gallery’s split levels, weaving together pounding beats, repetitive rhythms, voices counting numbers or reciting letters, audible breaths, and noises of uncertain origin. Drawn by these sounds, at once familiar and unsettling, visitors reach the third floor, where the three-channel video installation You may ask us who we are (2024) unfolds across screens. Images of Berlin’s aerodynamics laboratory and military leisure facilities built during the two World Wars appear alongside recreational sites in Korea that emerged during periods of economic development and now lie in ruin. These scenes are repeatedly pushed out of the frame by intervening hands and framing devices, only to surface again.[9] The work is grounded in audio recordings of Korean migrants from Russia made in German prisoner-of-war camps during the First World War, later preserved as wax cylinders in the Humboldt Forum’s Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv. As the voices of imprisoned captives, once compelled to speak before recording devices as historical evidence, resound in the present, the boundaries between nation and individual, past and present begin to blur, revealing their inherent instability.

Just as Heaven Baek’s Transcriptive Drawing (2026) series—composed of pen drawings paired with twenty-second videos—reveals, through the act of painstakingly transcribing strands of hair and the residual lines left behind, both the desire to record and fix a subject with clarity and the inherent incompleteness of that desire, this exhibition invites viewers not to follow the trajectory of each work in a linear manner, but to consider them within the shifting dynamics of relationships that are constantly misaligned and recalibrated.

— Sooyougn Leam (Independent Curator, Art Historian)

[1] Charles Fort, “The Book of the Damned,” in The Complete Books of Charles Fort: The Book of the Damned / New Lands / Lo! / Wild Talents, (New York: Dover Publications, 1974), p.3.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] For example, Kang Joohong, Haeven Baek, and Ha Min are women belonging to a particular generation, who are also classified as “emerging,” “mid-career,” or “senior” artists according to the criteria of Korea’s public funding programs. Their practices are often situated within various contextual frames: as artists who studied abroad or were trained domestically; within communities that do or do not accommodate caregiving responsibilities; or through associations with particular schools, small groups, media, or discourses to which they were once closely connected.

[5] Sang-gil Oh, ed., Rereading Korean Contemporary Art: A Critical Reappraisal of the Small-Group Movement of the 1980s (Seoul: Cheongeumsa, 2000), p.132.

[6] Minsu Ha, ed., HA. MINSU (Seoul: Nodemate, 2025), p.8. 30 Carat was a small collective formed in 1993 by women artists Kim Mikyung, Park Jisook, Ahn Miyoung, Yeom Jukyung, Lee Seungyeon, Lee Hyunmi, Lim Miryung, Choi Eunkyung, Ha Minsu, and Ha Sanglim.

[7] Kang Joohong, “unpublished artist statement,” 2026.

[8] Ha Minsu, “unpublished artist statement,” 2026.

[9] For more detailed information on You may ask us who we are, first presented at Heaven Baek’s solo exhibition Proxy State (Primary Practice, 2024), refer to: Heaven Baek, “Agentive Places, Proxy Bodies,” SeMA Coral. http://semacoral.org/features/heavenbaek-proxy-bodies